Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Reason and Atrocity: Hindriks’ Observation

Reason and Atrocity: Hindriks’ Observation

[email protected]

‘The massive threats to human welfare stem mainly from deliberate acts of principle, rather than from unrestrained acts of impulse’ (Bandura, 2002, p. 116).

‘The executioners, who face the most daunting moral dilemma, [...] adopted moral, economic, and societal security justifications for the death penalty’ (Osofsky, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2005, p. 387).

‘If we ask people why they hold a particular moral view [their] reasons are often superficial and post hoc. If the reasons are successfully challenged, the moral judgment often remains.’

‘basic values are implemented in our psychology in a way that puts them outside certain practices of justification [...] basic values seem to be implemented in an emotional way’

(Prinz, 2007, p. 32).

An inconsistent dyad

1. moral reasoning always only ever follows moral judgement

‘moral reasoning is [...] usually engaged in after a moral judgment is made, in which a person searches for arguments that will support an already-made judgment’ (Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008, p. 189).

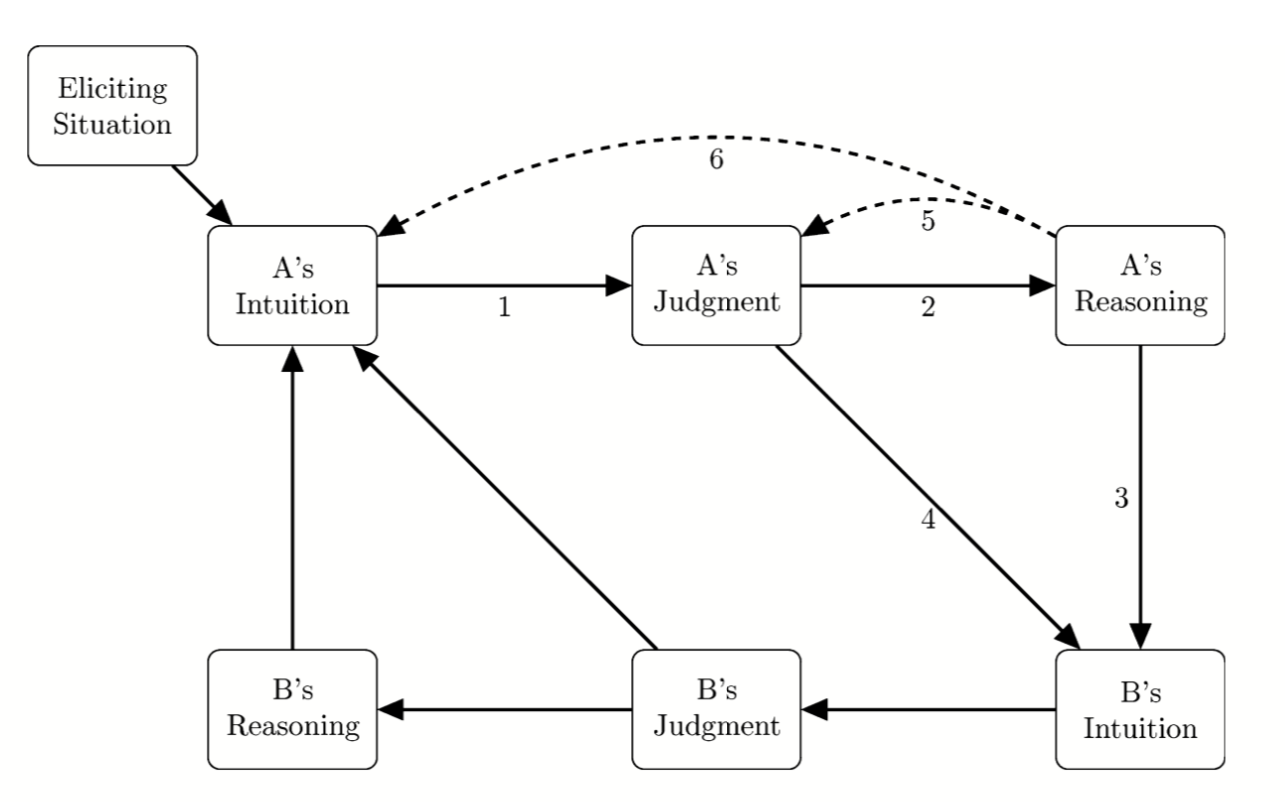

Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008 figure 4.1

An inconsistent dyad

1. moral reasoning always only ever follows moral judgement

‘moral reasoning is [...] usually engaged in after a moral judgment is made, in which a person searches for arguments that will support an already-made judgment’ (Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008, p. 189).

2. moral reasoning sometimes enables a moral judgement which would otherwise be impossible

Moral reasoning can overcome (i) affective support for judgements about not harming and (ii) affective obstacles to deliberately harming others.

significance?

Observations of the role of reason in enabling inhumane acts

appear to provide grounds sufficient to reject the view that

moral judgements are always, or even characteristically, entirely consequences of feelings.

puzzle

Why are moral judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?