Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Preview: Ethics vs Physics

Broadly perceptual processes

influence what seems obvious to you.

McCloskey et al. (1980, p. figure 2B)

McCloskey et al. (1980, p. figure 2D)

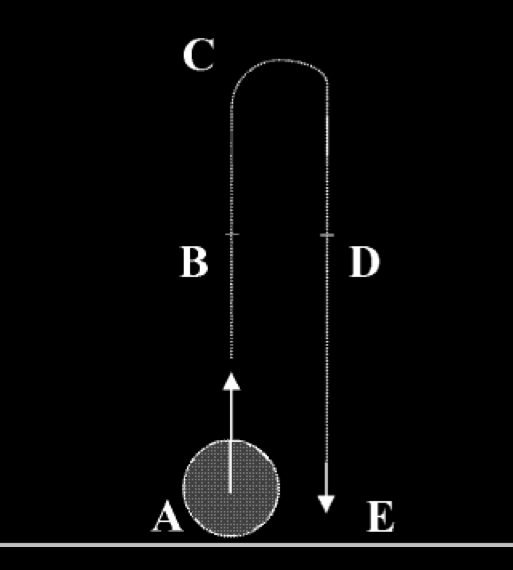

Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001, figure 1)

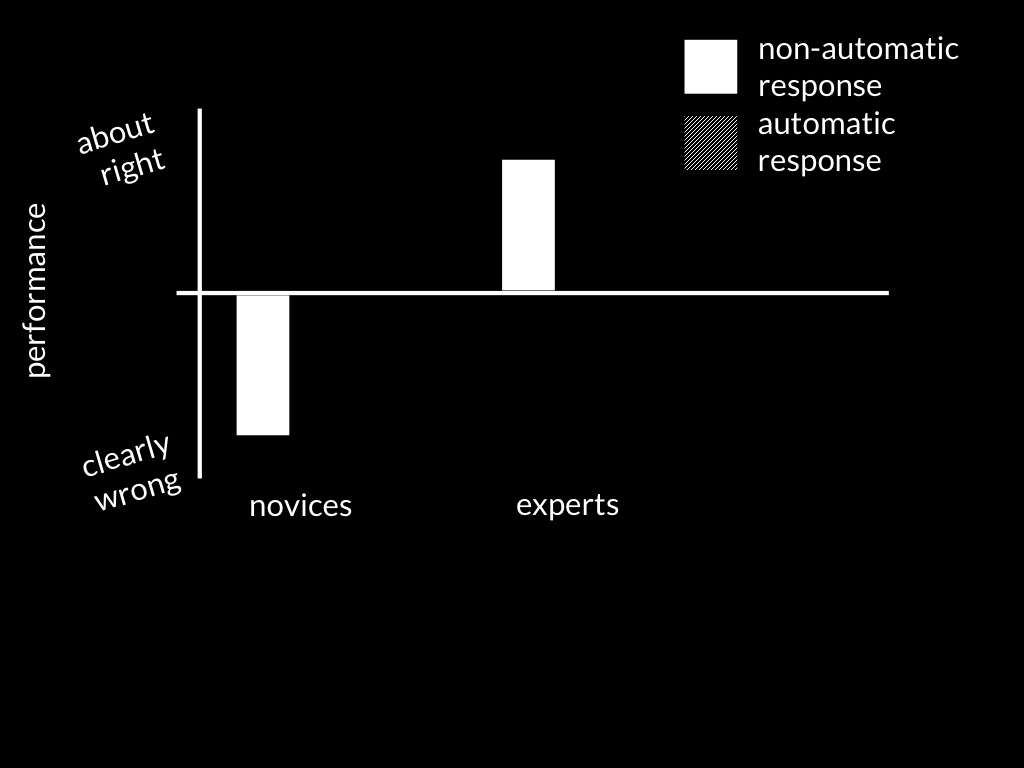

simplified from Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001)

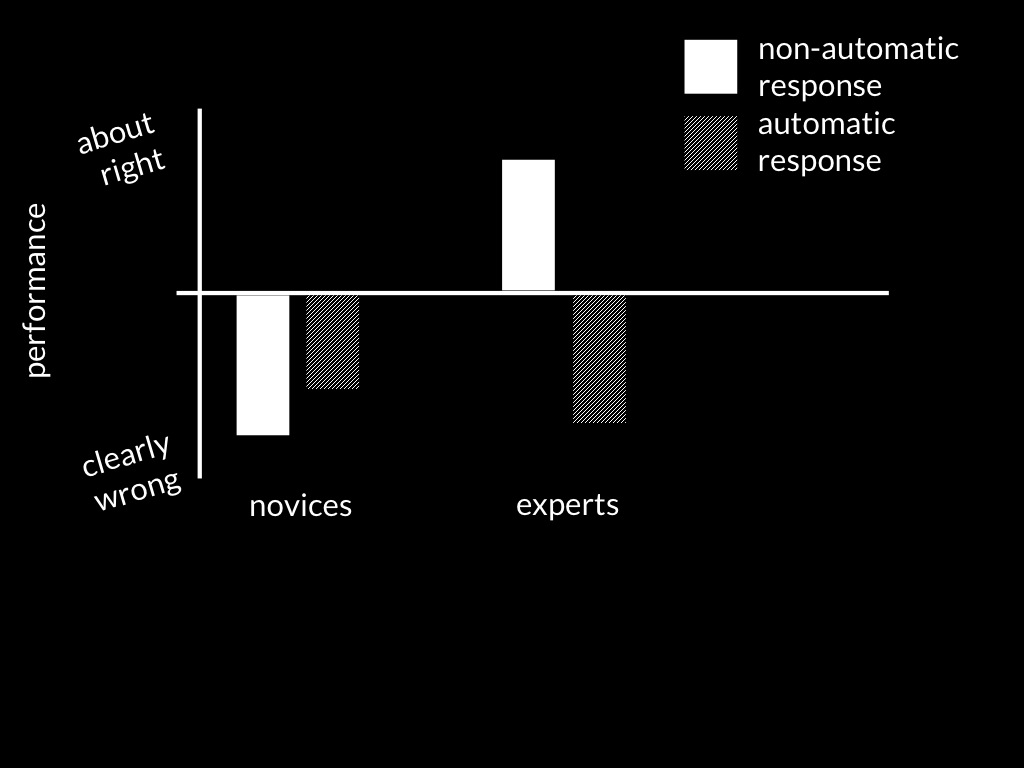

simplified from Kozhevnikov & Hegarty (2001)

speed vs accuracy

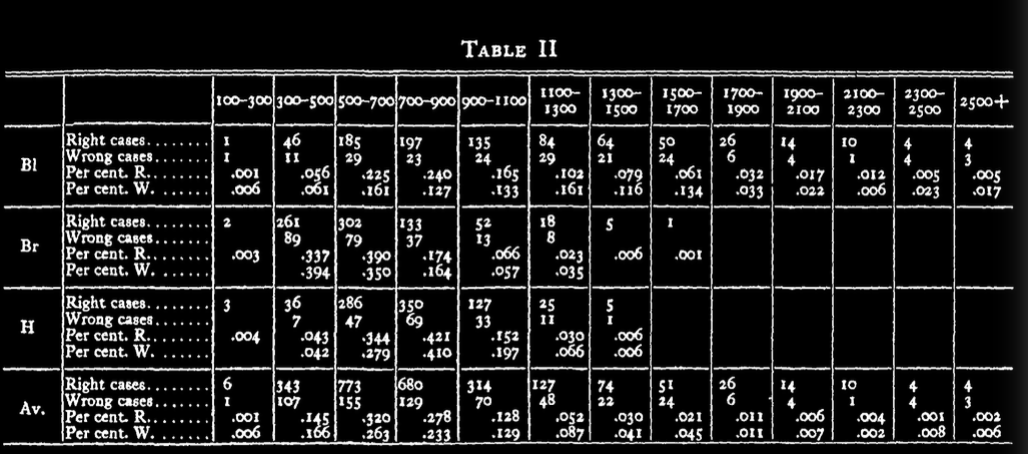

Henmon (1911, table 2)

‘To extrapolate objects’ motion on the basis of [e.g. Newtonian] physical principles, one should have assessed and evaluated the presence and magnitude of such imperceptible forces as friction and air resistance ... This would require a time-consuming analysis that is not always possible.

‘In order to have a survival advantage, the process of extrapolation should be fast and effortless, without much conscious deliberation.

‘Impetus theory allows us to extrapolate objects’ motion quickly and without large demands on attentional resources.’

Kozhevnikov and Heggarty (2001, p. 450)

ethics?

If we applied Thomson’s method (or Rawls’) in the case in attempting to discover things about the physical world, we would unable to do things like landing a robot on a comet.

If we applied Thomson’s method (or Rawls’) in the case in attempting to discover things about ethical principles, we would unable to deal with unfamiliar problems.

This is because whether something seems obvious (even after much reflection---see Aristotle) depends on fast processes. And fast processes gain speed by sacrificing accuracy.

Thomson’s method

[premise] There is a morally relevant difference between David and Edward.

[premise] There is no morally relevant difference between Edward and Frank.

[premise] ...

[conclusion] Thomson’s principle better explains the moral facts than Foot’s principle.

(how) do I know?