Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Moral Dumbfounding

What is moral dumbfounding?

Haidt et al (2000; unpublished!)’s tasks

Control: ‘Heinz dilemma (should Heinz steal a drug to save his dying wife?)’

morally provocative but ‘harmless’: Incest; Cannibal

nonmorally provocative but ‘harmless’: Roach; Soul

Method: ask whether wrong; counter argue; questionnaire

Results

NB: unpublished data

‘it often happened that participants made “unsupported declarations”, e.g., “It’s just wrong to do that!” or “That’s terrible!”

They made the fewest such declarations in Heinz, and they made significantly more such declarations in the Incest story.’

Results ctd

NB: unpublished data

Informal observation: ‘participants often directly stated that they were dumbfounded, i.e., they made a statement to the effect that they thought an action was wrong but they could not find the words to explain themselves’ (p. 9)

‘Participants made the fewest such statements in Heinz (only 2 such statements, from 2 participants), while they made significantly more such statements in the Incest (38 statements from 23 different participants), Cannibalism (24 from 11), and Soul stories (22 from 13).’

Study 2 (not reported!):

Cognitive load increased the level of moral dumbfounding without changing subjects’ judgments.

replication / extension / review?

‘a definitionally pristine bout of MD is likely to be a extraordinarily rare find, one featuring a person who doggedly and decisively condemns the very same act that she has no prior normative reasons to dislike’

Royzman et al, 2015 p. 311

‘3 of [...] 14 individuals [without supporting reasons] disapproved of the siblings having sex and only 1 of 3 (1.9%) maintained his disapproval in the “stubborn and puzzled” manner.’

Royzman et al, 2015 p. 309

Warning: Note the absent comparison with the Heinz dilemma.

another replication

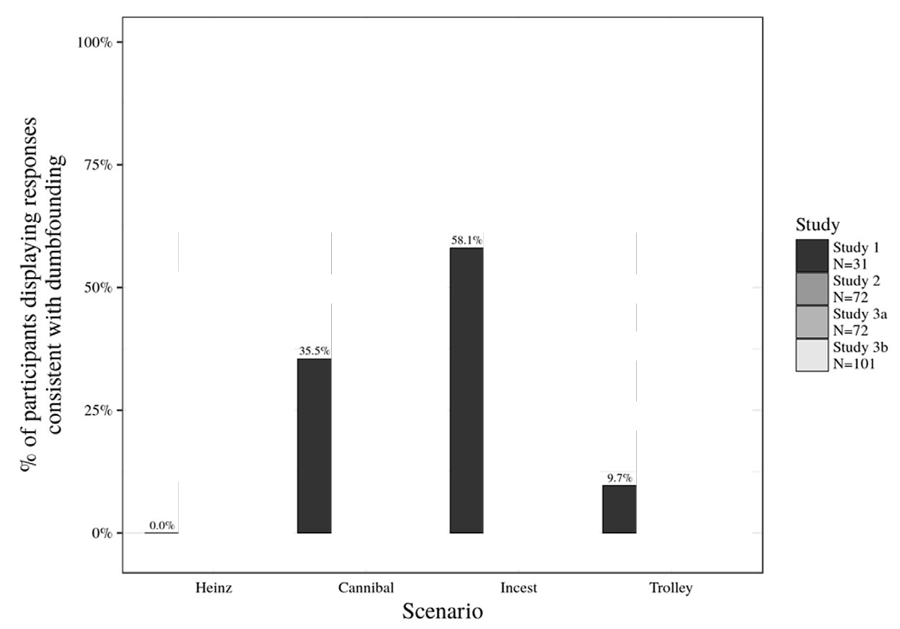

McHugh, McGann, Igou, & Kinsella (2017, p. figure 1, part)

further replications

see notes on handout

replication / extension / review?

diy approach (!)

replication / extension / review?

| place | most dumbfounding scenario | ||

| Trolley | Cannibal | Incest | |

| India | x | ||

| Middle East and North Africa | x | ||

| China | x | ||

| WEIRD | x | ||

while for the Chinese sample, Cannibal evoked the highest rates of dumbfounding.

In contrast for WEIRD samples, Incest tends to be the scenario that most reliably evokes dumbfounding

(McHugh, Zhang, Karnatak, Lamba, & Khokhlova, 2023, p. 1056)

replication / extension / review?

summary: moral dumbfounding

we know the definition;

some evidence — not rock solid, but probably occurs.