Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Cognitive Miracles: When Are Fast Processes Unreliable?

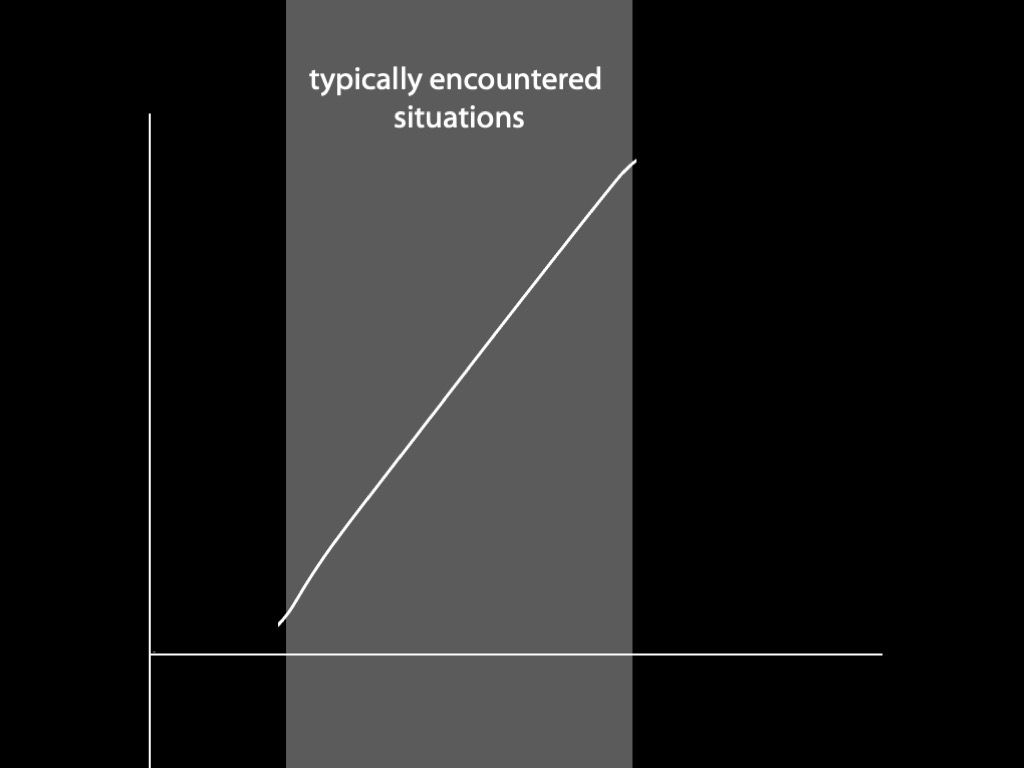

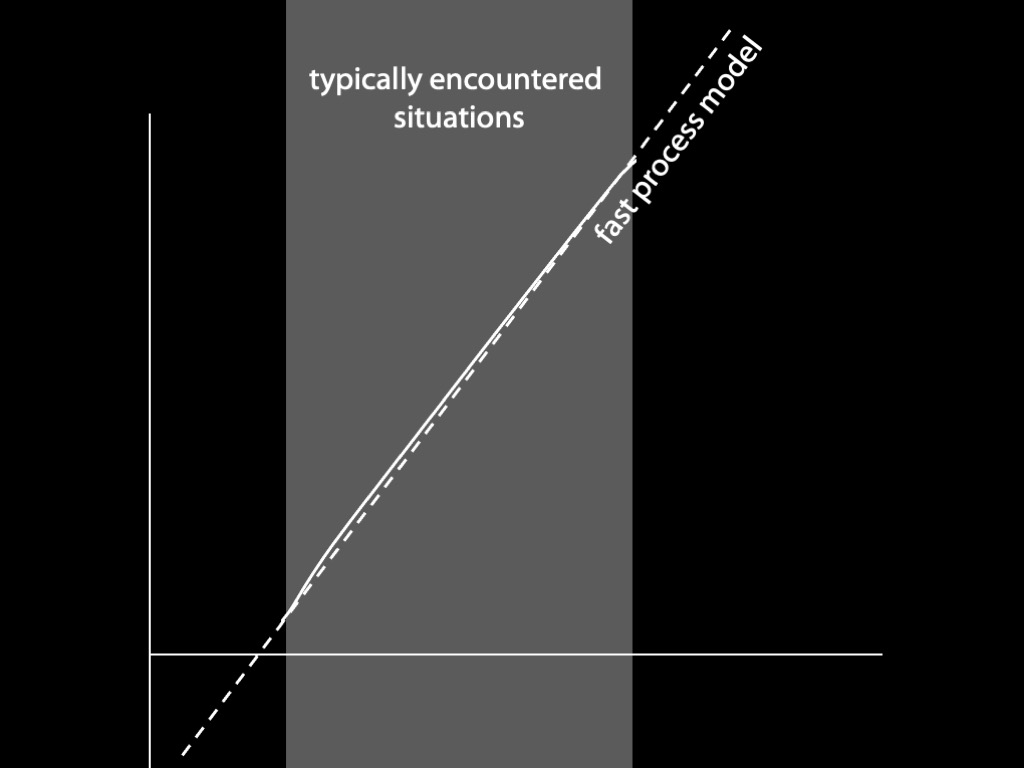

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

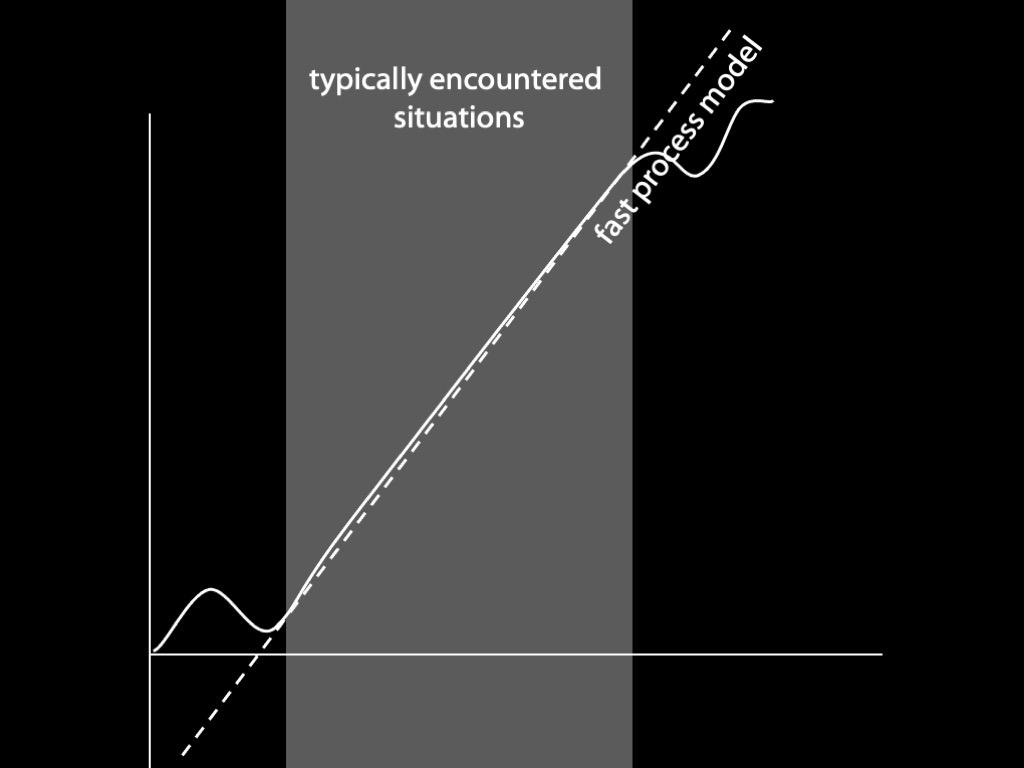

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

‘genetic transmission,

cultural transmission,

and learning from personal experience

[...] are the only mechanisms known to endow [fast]

processes with the information they need to function well’

(Greene, 2014, p. 714)

unfamiliar* problems = ‘ones with which we have inadequate evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience’

‘Frank is a passenger on a trolley whose driver has just shouted that the trolley's brakes have failed, and who then died of the shock. [...] Frank can turn the trolley, killing the one; or he can refrain from turning the trolley, letting the five die’ (Thomson, 1976, p. 207).

May Frank turn the trolley?

‘it would be a cognitive miracle if we had reliably good moral instincts about unfamiliar* moral problems’

‘The No Cognitive Miracles Principle:

When we are dealing with unfamiliar* moral problems, we ought to rely less on [...] automatic emotional responses and more on [...] conscious, controlled reasoning, lest we bank on cognitive miracles.’

Greene, 2014 p. 715

Compare the physical case.

Fast processes are characterised by principles of Impetus mechanics

which yield correct predictions in some unfamiliar* cases, including

point-light displays, and

cartoons

unfamiliar problems (or situations): ‘ones with which we have inadequate evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience’

‘The No Cognitive Miracles Principle:

When we are dealing with unfamiliar* moral problems, we ought to rely less on [...] automatic emotional responses and more on [...] conscious, controlled reasoning, lest we bank on cognitive miracles.’

Greene, 2014 p. 715

unfamiliar* problems = ‘ones with which we have inadequate evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience’

1. Unfamiliarity* depends on inadequacy [by definition]

2. We do not know which evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience is inadequate (unless we know how the faster processes work)

3. Therefore, we do not know which problems are unfamiliar [from 1, 2]

4. Therefore, we can make no practical use of the No Cognitive Miracles Principle

?

fully-informed disagreement about what to do

as a proxy for unfamiliarity

(Greene, 2014, p. 716)

1. Unfamiliarity* depends on inadequacy [by definition]

2. We do not not which evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience is inadequate (unless we know how the faster processes work)

3. Therefore, we do not know which problems are unfamiliar [from 1, 2]

4. Therefore, we can make no practical use of the No Cognitive Miracles Principle [from 3]

wicked learning environments

‘When a person’s past experience is both representative of the situation relevant to the decision and supported by much valid feedback, trust the intuition; when it is not, be careful’

(Hogarth, 2010, p. 343).

action at a distance

weapons of mass destruction (Thomson, 1976)

...

speed vs accuracy trade-offs

1. Unfamiliarity* depends on inadequacy [by definition]

2. We do not not which evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience is inadequate (unless we know how the faster processes work)

3. Therefore, we do not know which problems are unfamiliar [from 1, 2]

4. Therefore, we can make no practical use of the No Cognitive Miracles Principle [from 3]

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.