Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Do Ethical Attitudes Shape Political Behaviours?

Do Ethical Attitudes Shape Political Behaviours?

[email protected]

1

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

background: effect size

significance vs effect size

illustration

To what extent does being a climate sceptic make you less likely to support measures to mitigate climate change?

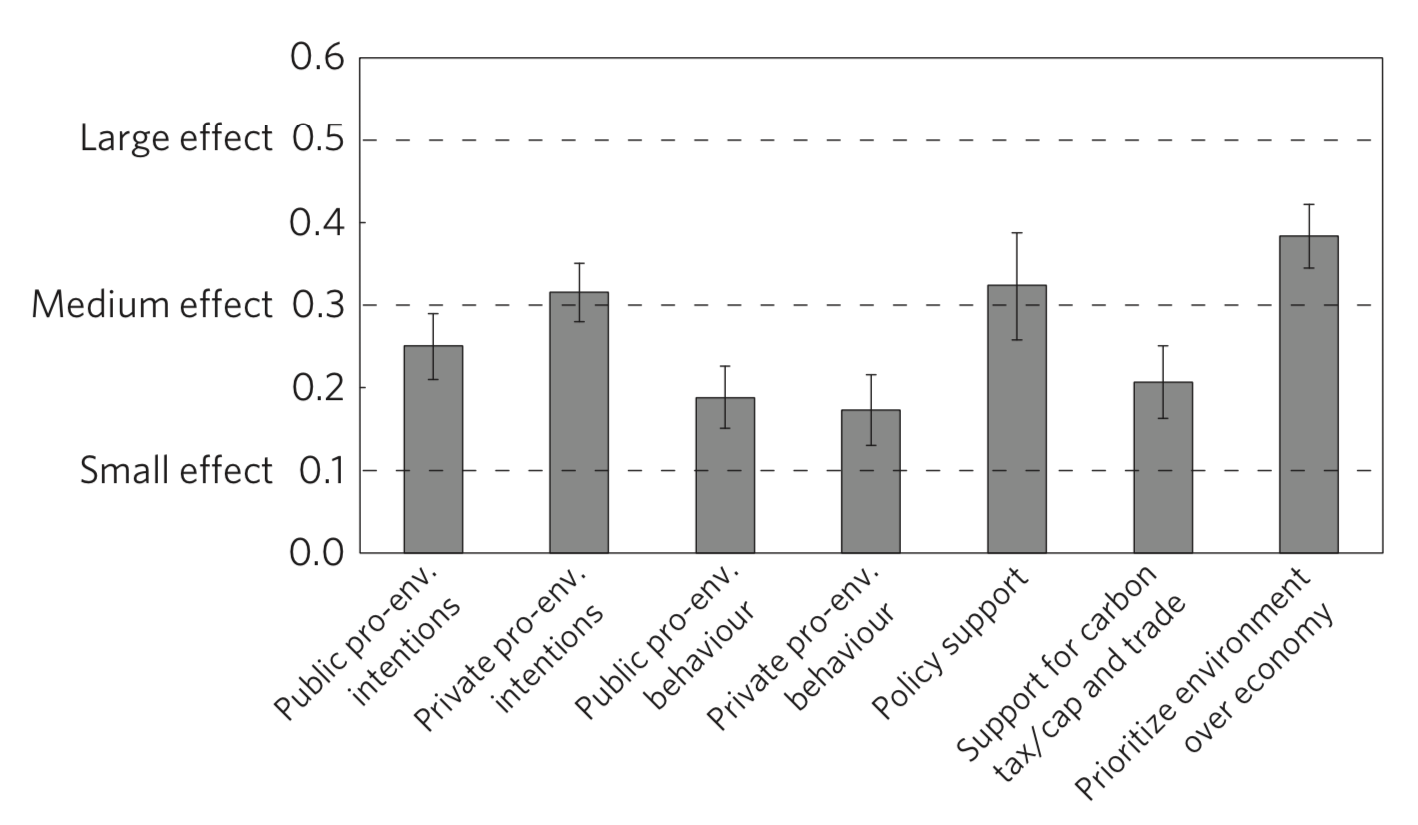

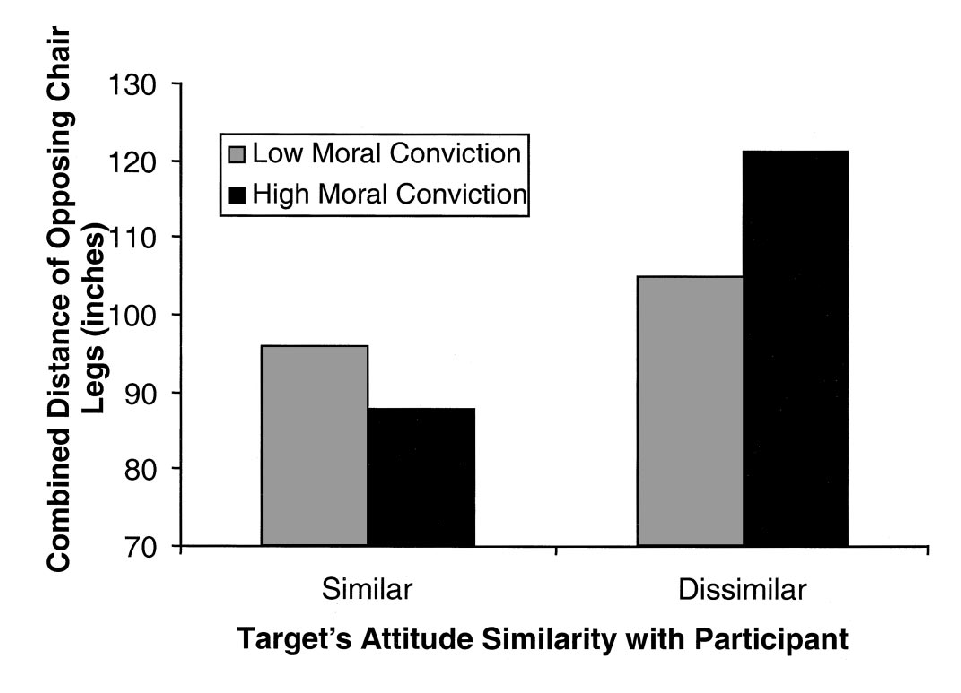

Hornsey, Harris, Bain, & Fielding (2016, p. figure 3)

‘believers [in climate change] are more likely than skeptics to report that they intend to behave in climate-friendly ways (r = .32) but on actual behaviors the difference is modest (r = .17).’

In other words, knowing whether people are skeptics or believers tells you surprisingly little about their willingness to engage in actions that matter’

‘For example, the difference between believers and skeptics in terms of their willingness to put a price on carbon is relatively small (r = .20)’

(Hornsey & Fielding, 2020, p. 21).

1

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

steps

1. Your convictions do not explain much of your behaviour.

2. Your moral convictions do explain much more of your behaviour.

it is considerably more likely that attitudes will be unrelated or only slightly related to overt behaviors than that attitudes will be closely related to actions’

‘Only rarely can as much as 10% of the variance in overt behavioral measures be accounted for by attitudinal data.

In studies in which data are dichotomized, substantial proportions of subjects show attitude-behavior discrepancies.

This is true even when subjects scoring at the extremes of attitudinal measures are compared on behavioral indices.’

Wicker (1969, p. 65)

racism and mild torture

(Genthner & Taylor, 1973)

Participants: 36 males, 18 high/18 low prejudice scores

Measure prejudice and then allow subjects to administer electric shocks to opponents in a game.

Will more prejudiced subjects differentiate between Black and White opponents?

Background: ‘The traditional social learning model posits that a negative attitude [...] facilitates aggression toward a disliked person’

Results: ‘While the low-prejudiced subjects behaved in a relatively nonaggressive manner toward both the Black opponents and the White opponents, the high-prejudiced subjects aggressed equally against’ both

Genthner & Taylor, 1973 p. 209

That research is really old!

What’s the state of the art now

on whether attitudes predict behaviours?

1

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes (Emler, 2003; Mullen & Skitka, 2006; Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005)’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005

‘People’s feelings about various sports teams, their musical tastes, or even their relative preference for Mac versus PC operating systems could each easily be experienced as strong attitudes (extreme, certain, etc.), but would rarely be experienced as moral. People’s feelings about infanticide, female circumcision, abortion, or a host of political issues (gay marriage, the Iraq War, the Patriot Act), however, could be experienced as both strong and moral.’

Skitka & Bauman, 2008 p. 31

Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005

‘we conducted four studies that examined whether strength of moral conviction predicted unique variance beyond other indices of attitude strength, such as attitude extremity, importance, certainty, and centrality, on a number of interpersonal measures’

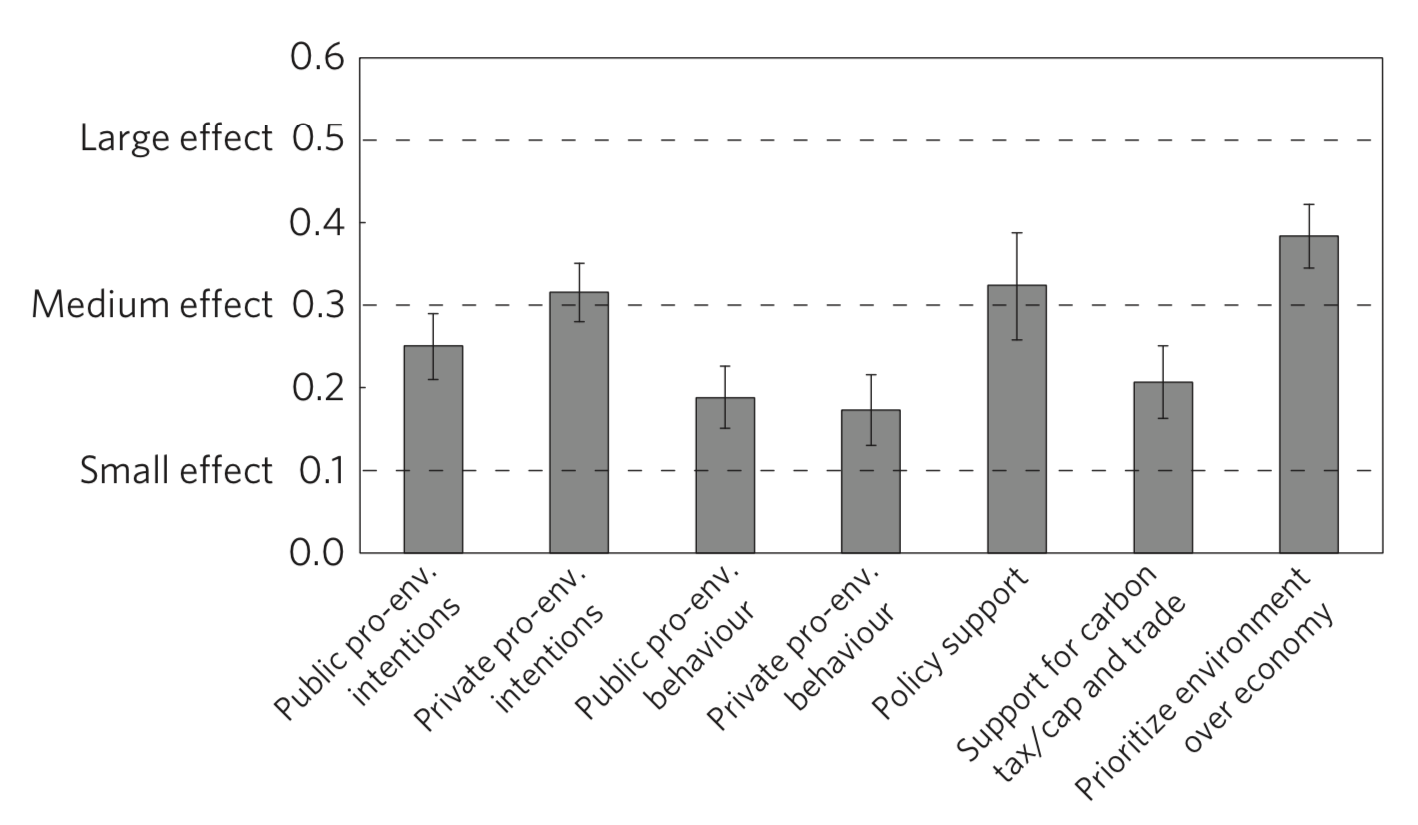

‘exploring whether people prefer greater social [studies 1 & 2; and physical: study 3] distance from attitudinally dissimilar others when the attitude domain was held with high rather than low moral conviction’

Skitka et al. (2005, p. figure~1)

Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005

Results of Study 1:

‘The effect of moral conviction on social distance was robust when we controlled for the effects gender, age, attitudinal extremity, importance, and centrality’

‘In contrast, participants were more tolerant of having a distant than an intimate relationship with an attitudinally dissimilar other, when the attitude dissimilarity was on an issue that the participant held with low moral conviction, results that held even when we controlled for attitude strength.’

Background:

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes (Emler, 2003; Mullen & Skitka, 2006; Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005)’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

Evidence?!

Never trust a philosopher scientist.

steps

1. Your convictions do not explain much of your behaviour.

2. Your moral convictions do explain much more of your

behaviour.

Do specifically moral attitudes influence voting behaviour?

‘moral conviction about candidate preferences also uniquely increased the odds of voting, even when controlling for effects of candidate preference, party identification, strength of candidate preference, strength of party identification, and demographic variables.

‘As strength of moral conviction about one’s candidate preference increased, so did the likelihood that one voted’

Study 2: voting intentions

In both studies: ‘the effects of moral conviction on political engagement were equally strong for those on the political right and left’

Skitka & Bauman, 2008 pp. 42, 50

1

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes (Emler, 2003; Mullen & Skitka, 2006; Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, 2005)’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

What about political attitudes to climate change specifically?

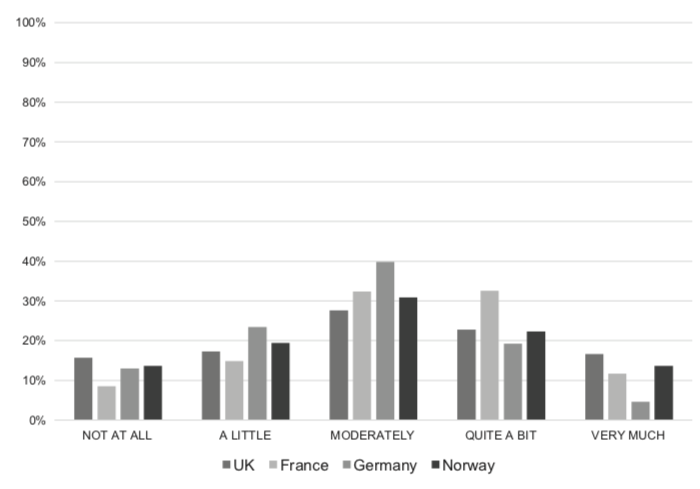

[consequences] ‘Overall, how positive or negative do you think the effects of climate change will be on [COUNTRY]?’.

[ethical concern] ‘Some people have moral concerns about climate change. For example, because they think that its harmful impacts are more likely to affect poorer countries, or because they feel a moral responsibility towards future generations. To what extent, if at all, do you have moral concerns about climate change?’

Doran et al, 2019 figure 2

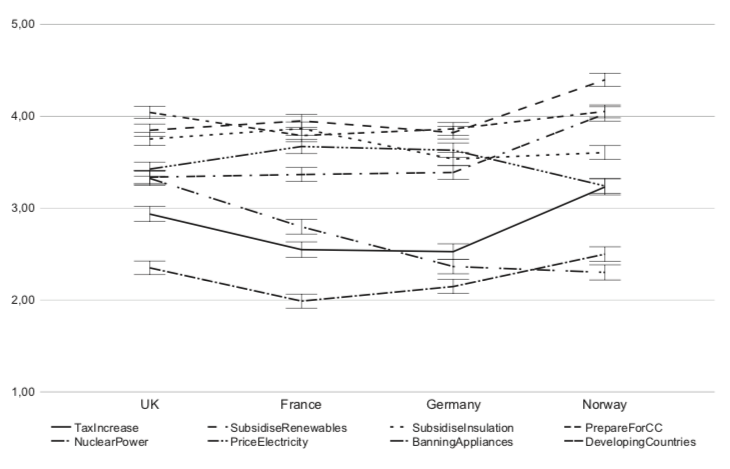

[policies] ‘To what extent do you support or oppose the following policies in [COUNTRY]?’

Doran et al, 2019

Doran et al, 2019 figure 3

Results

‘individuals with strong moral concerns about climate change tend to be more likely to support climate policies.

moral concerns turned out to be substantially more important than consequence evaluations, explaining about twice as much of the variance.’

Implication: ‘threat raising campaigns may not be the preferred strategy to encourage public engagement with climate change’

1

‘Moral convictions and the emotions they evoke shape political attitudes’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1