Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Ethical Implications of the Dual Process Theory

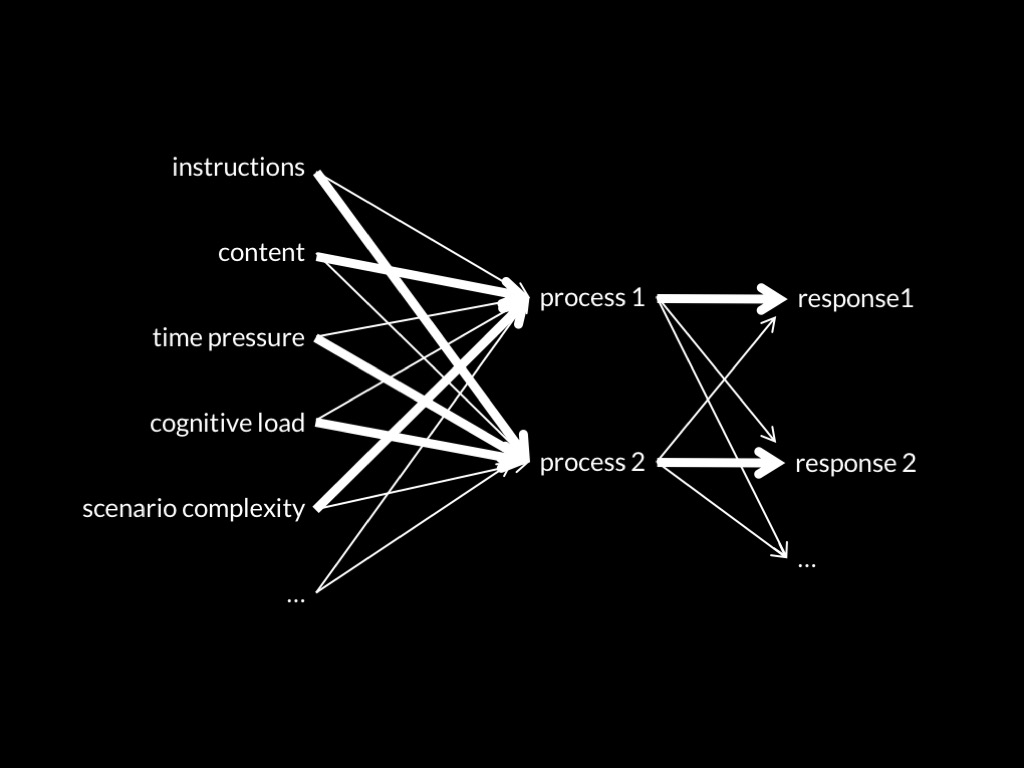

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

negative: object to arguments against consequentialism

positive : support for consequentialism

‘the chief weapons of opponents of utilitarianism have been examples intended to show that the dictates of utilitarianism clash with moral intuitions that we all share’

(Singer, 2005, p. 343)

Against Consequentialism

Many spontaneously judge that we should not Drop.

Therefore:

We should not Drop.

Consequentialism* implies we should Drop.

Therefore:

Consequentialism* is wrong.

Drop

Mary [...] notices an empty boxcar rolling out of control. [...] anyone it hits will die. [...] If Mary does nothing, the boxcar will hit the five people on the track. If Mary pulls a lever it will release the bottom of the footbridge and [...] one person will fall onto the track, where the boxcar will hit the one person, slow down because of the one person, and not hit the five people farther down the track.

Pulling the lever is: [extremely morally good:::neither good nor bad:::extremely morally bad]

negative: object to arguments against consequentialism

positive : support for consequentialism

1. Slow processes are consequentialist.

2. Slow is better than fast when there is disagreement.

Therefore:

3. Consequentialism is true

(not one of Greene’s arguments)

negative: object to arguments against consequentialism

positive : support for consequentialism

1. ‘Most, if not all, of act consequentialism’s competition’ relies on premises that are not-justified-inferentially

2. Consequentialism does not rely on any such premises

Therefore:

3. Consequentialism is true

compare Greene (2014, p. 725)

negative: object to arguments against consequentialism

positive : support for consequentialism