Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

A Dual Process Theory of Ethical Judgement

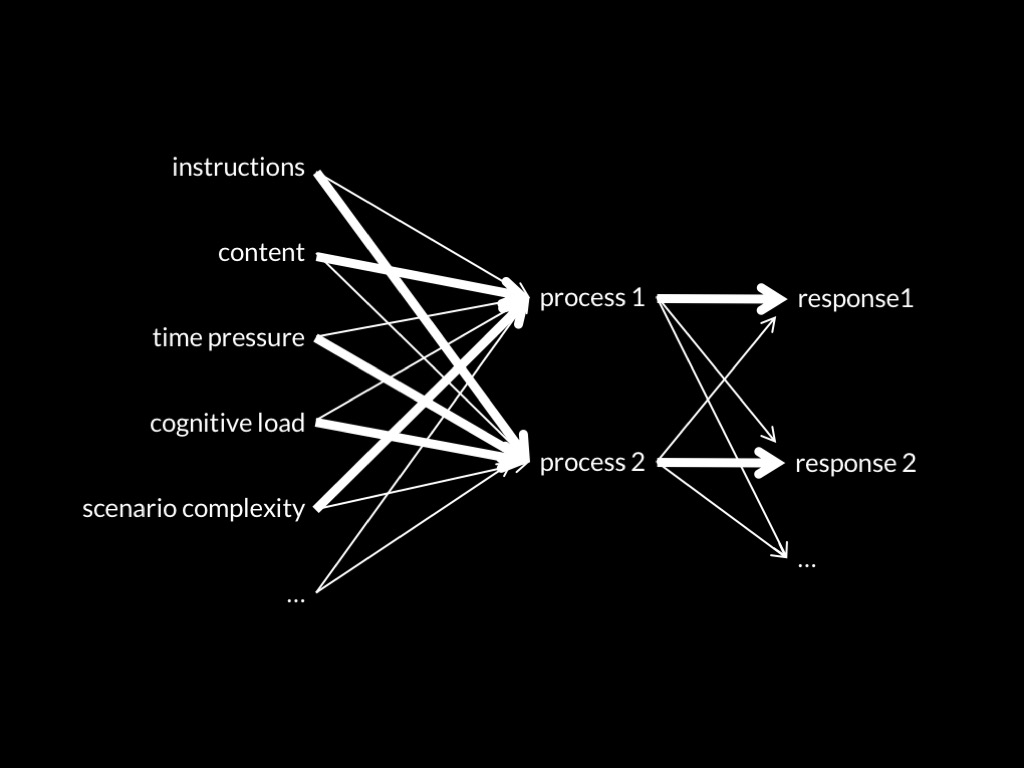

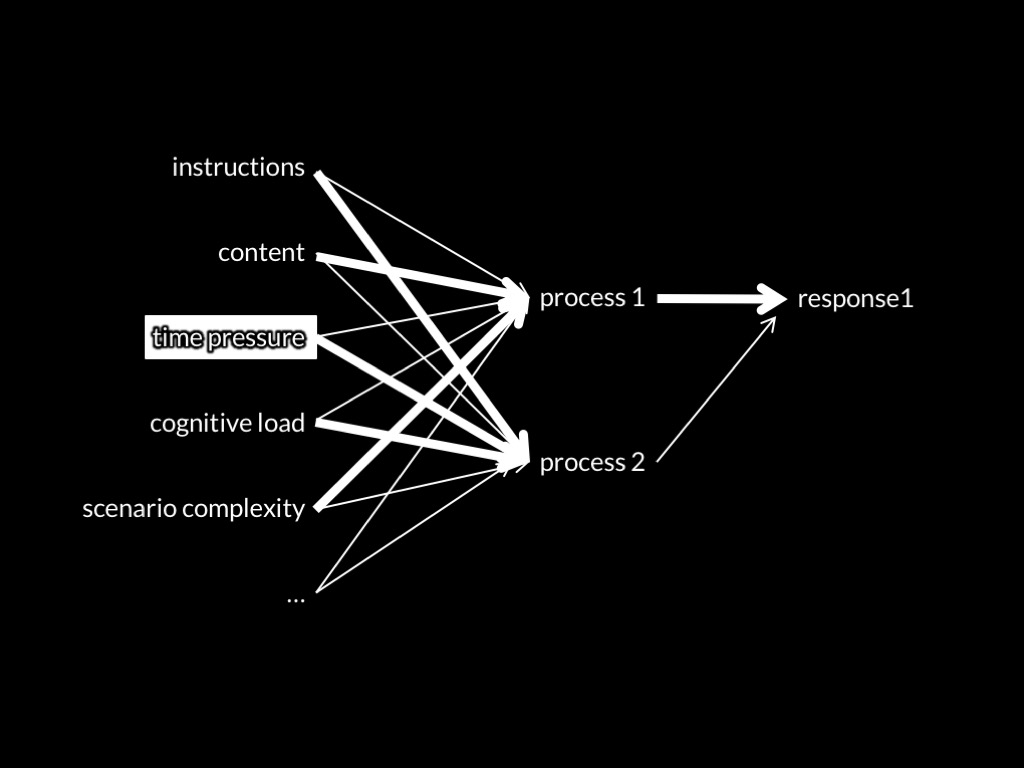

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

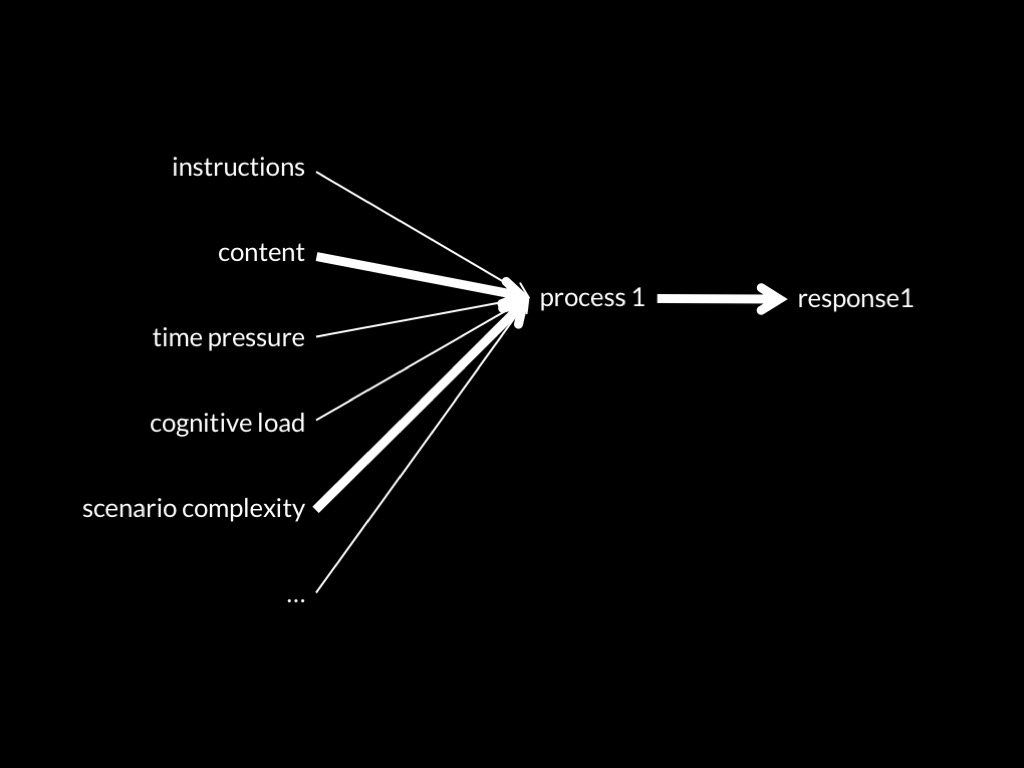

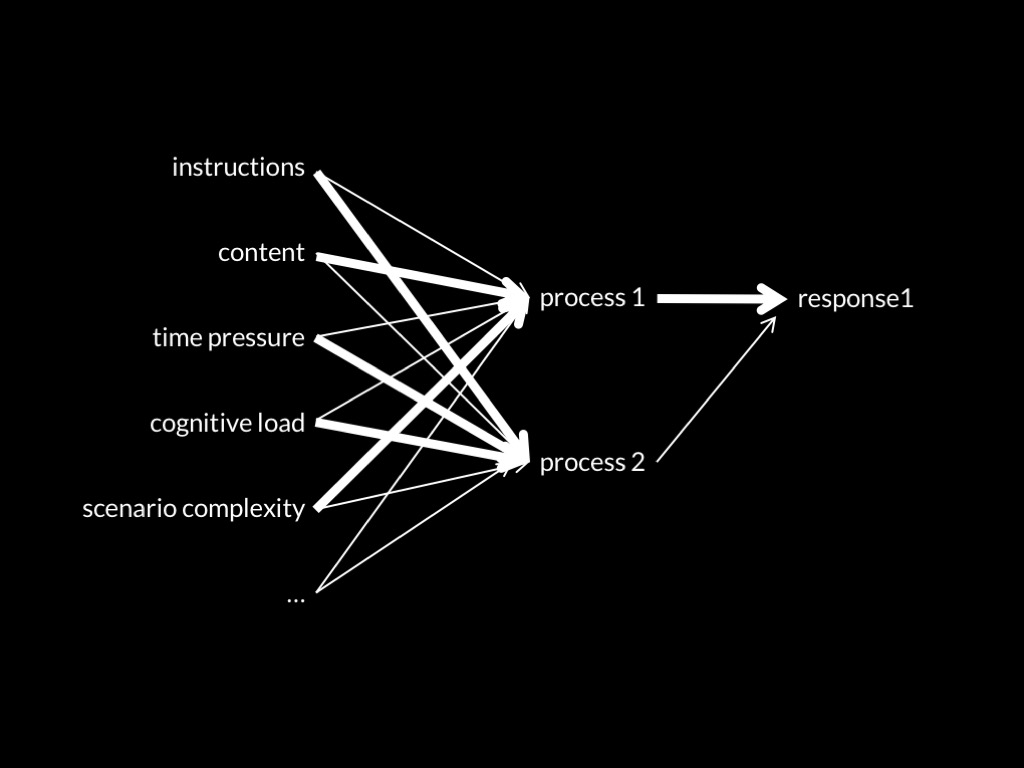

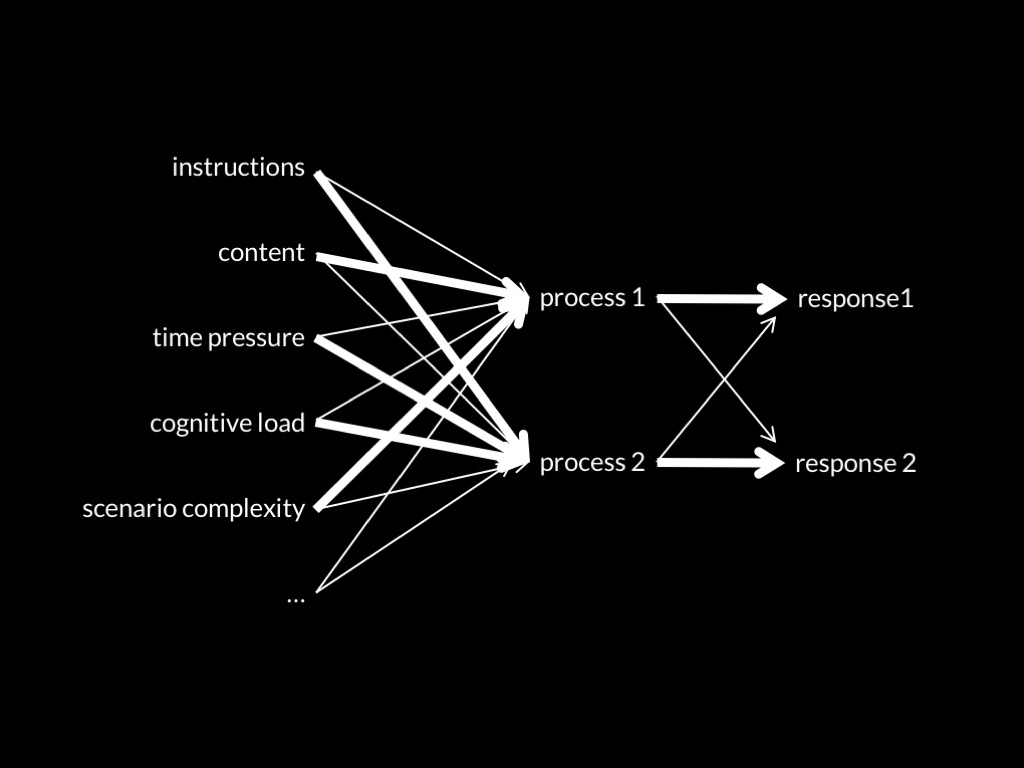

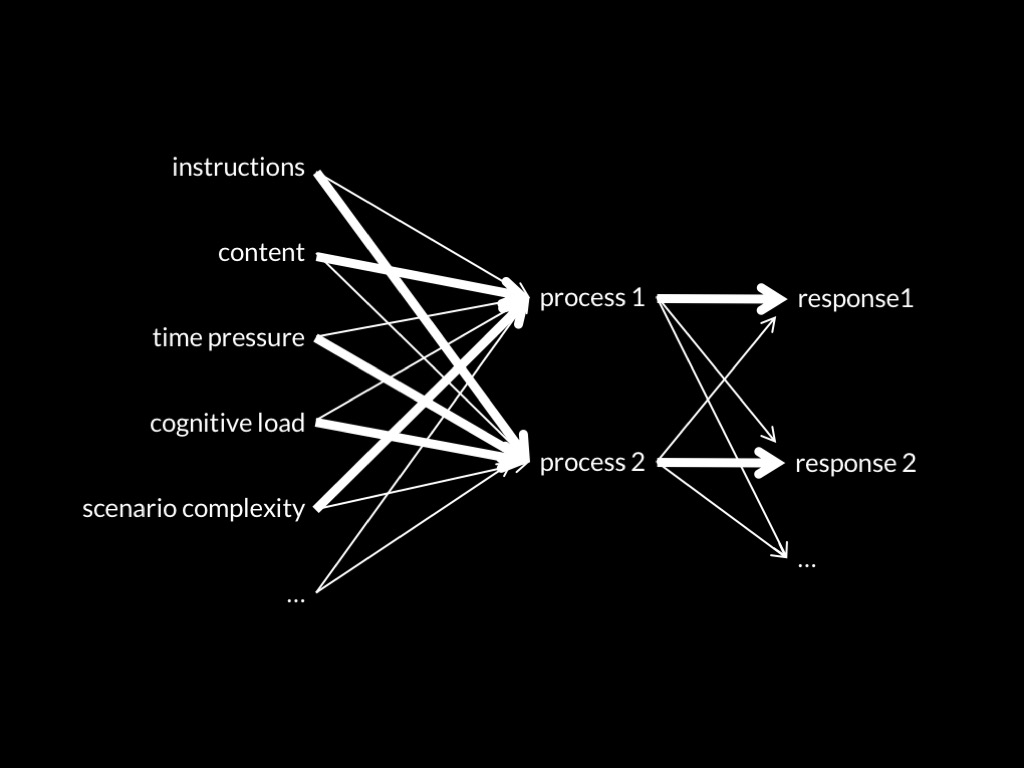

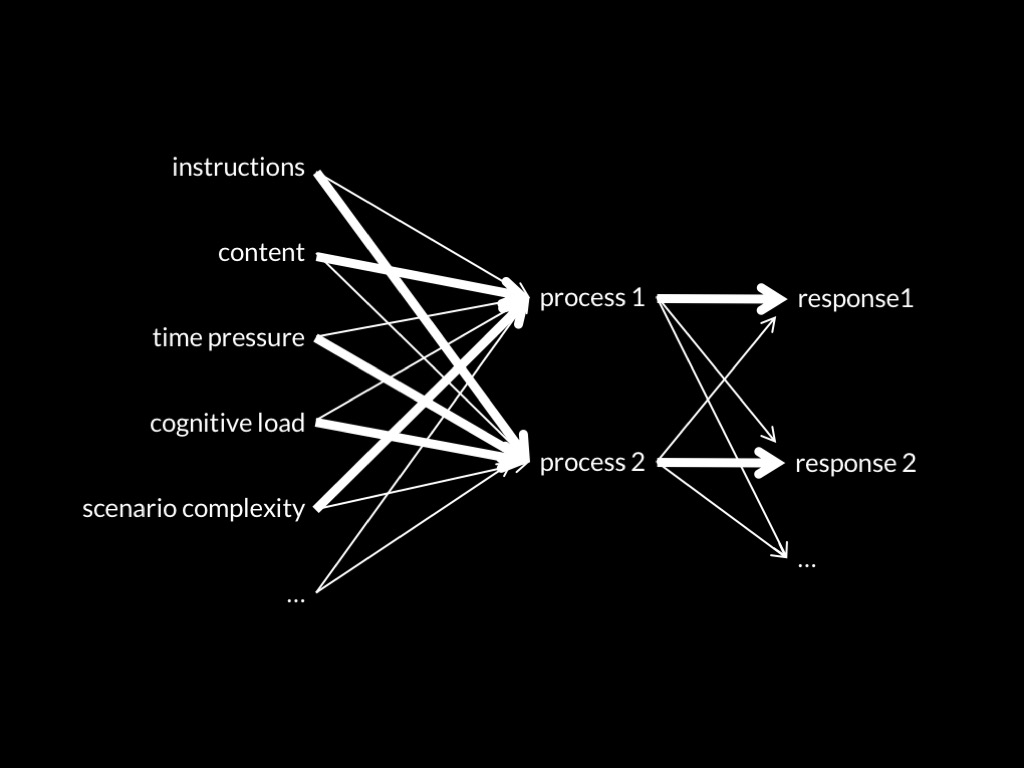

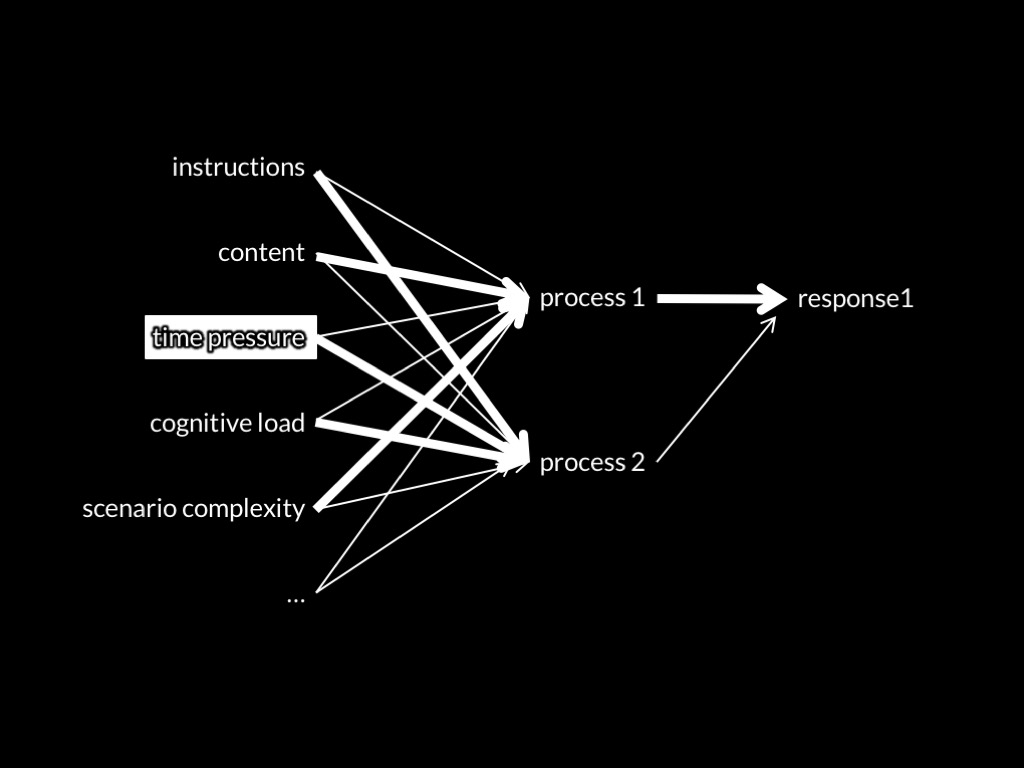

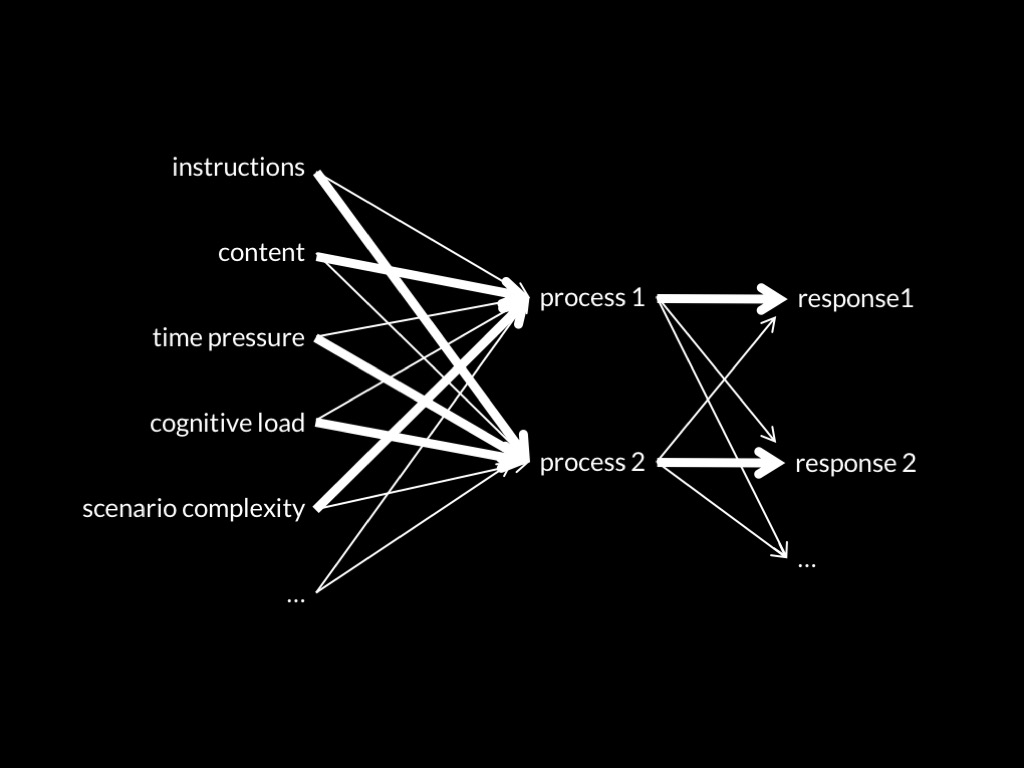

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

Additional assumption

The slow process is responsible for characteristically consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

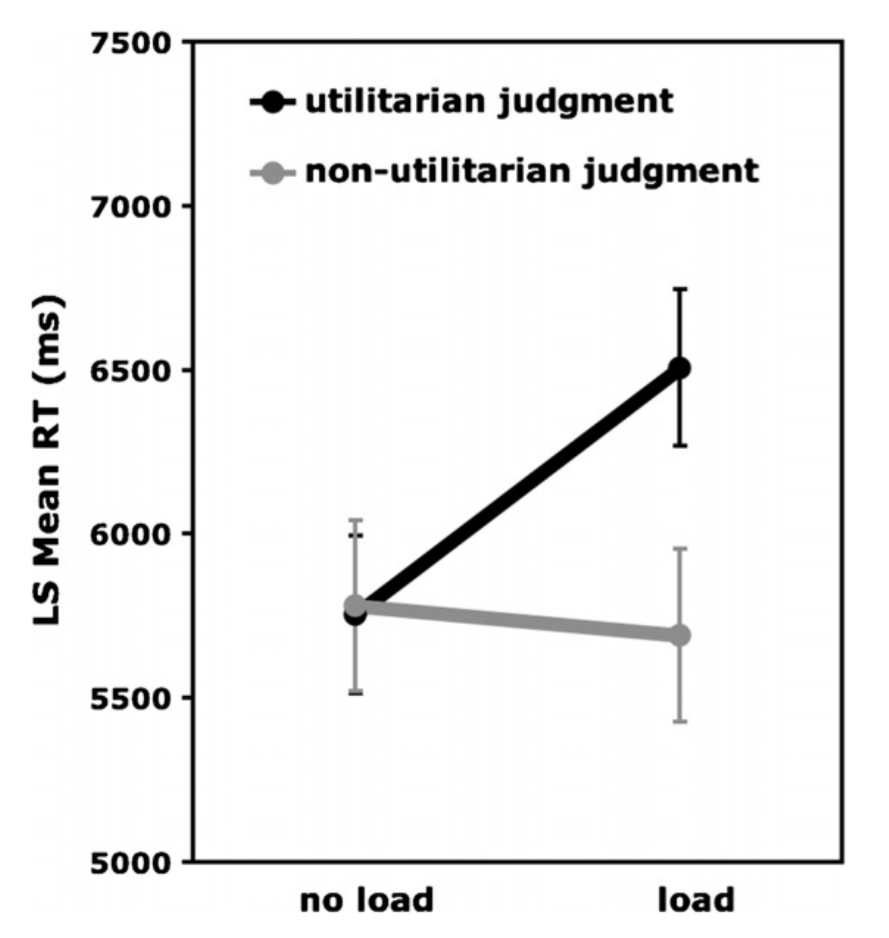

Prediction: Increasing cognitive load will selectively slow consequentialist responses

Greene et al 2008, figure 1

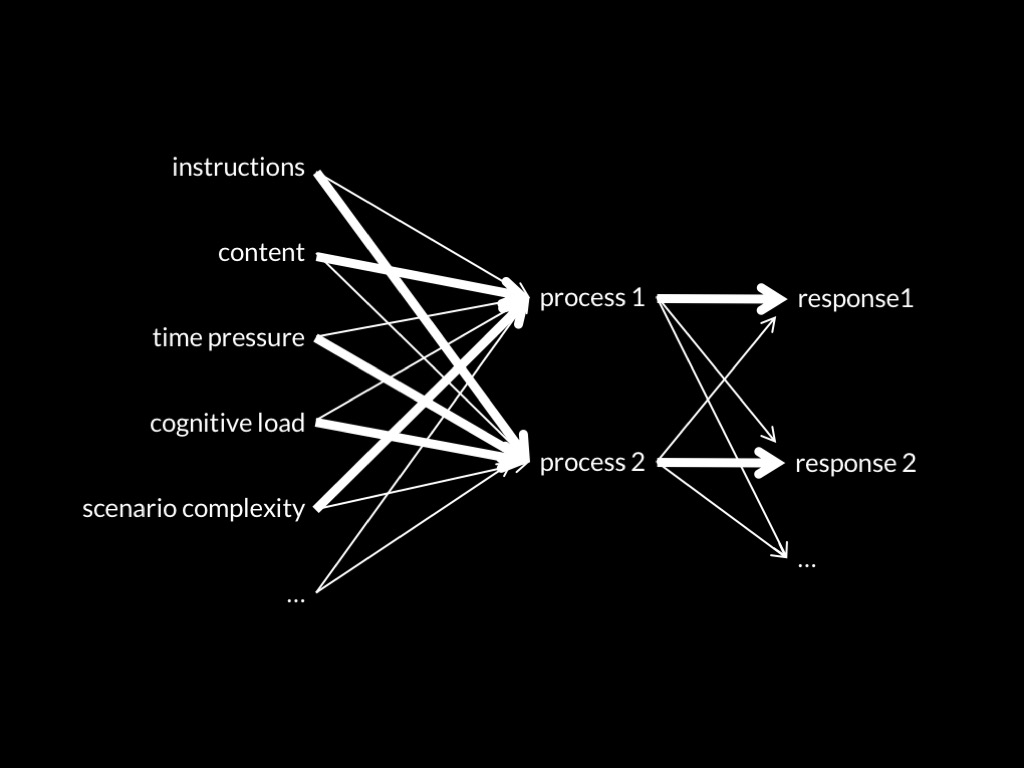

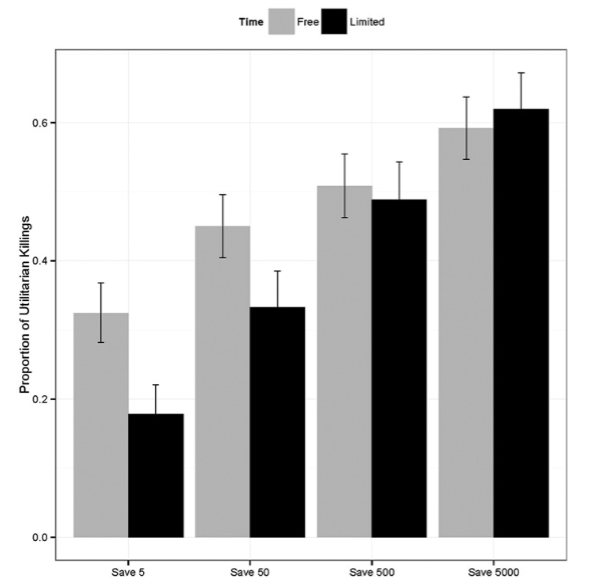

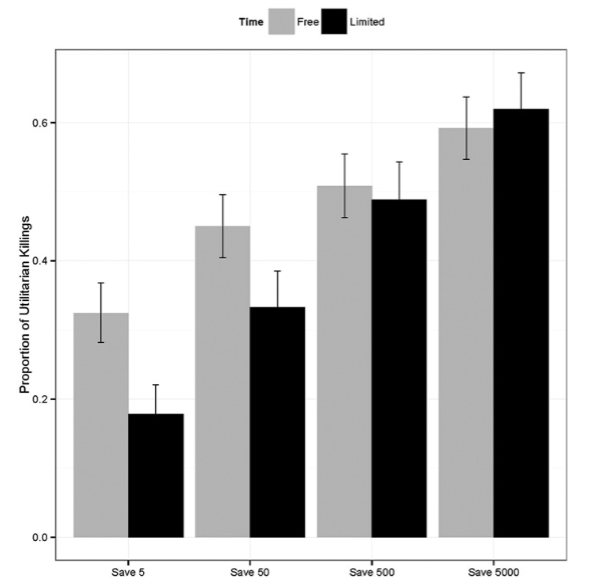

Additional assumption

The slow process is responsible for consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

Prediction: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

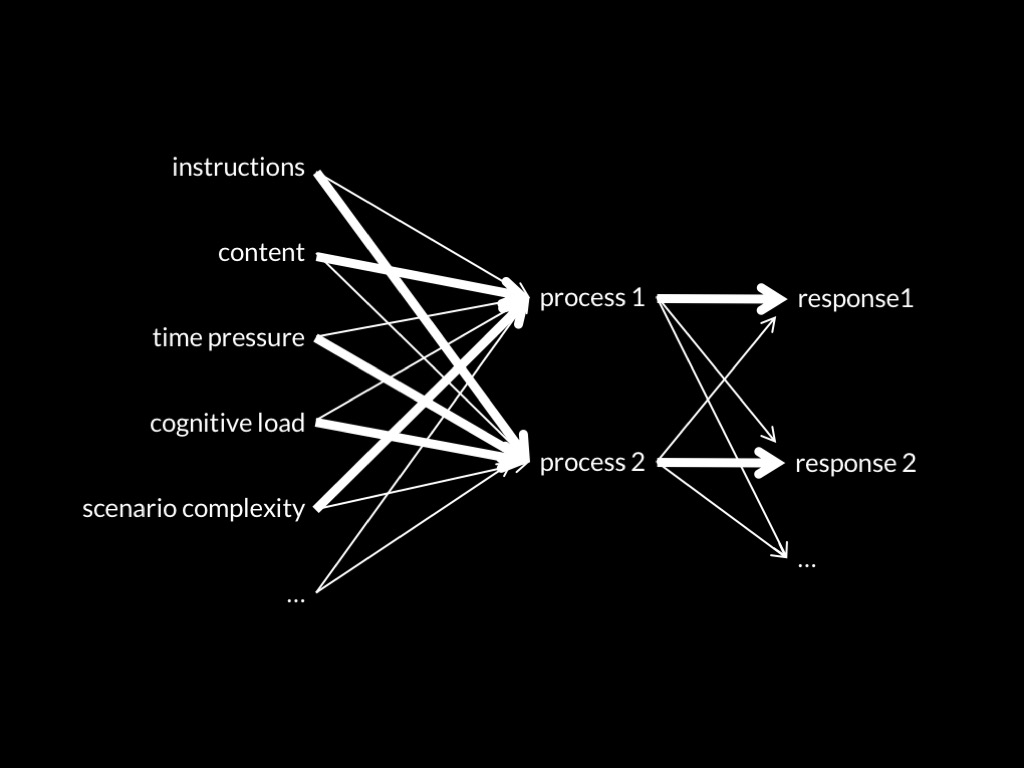

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

[Aside : camera analogy]

‘it’s worth highlighting three ways in which the camera analogy may mislead’

Greene, 2014 p. 698

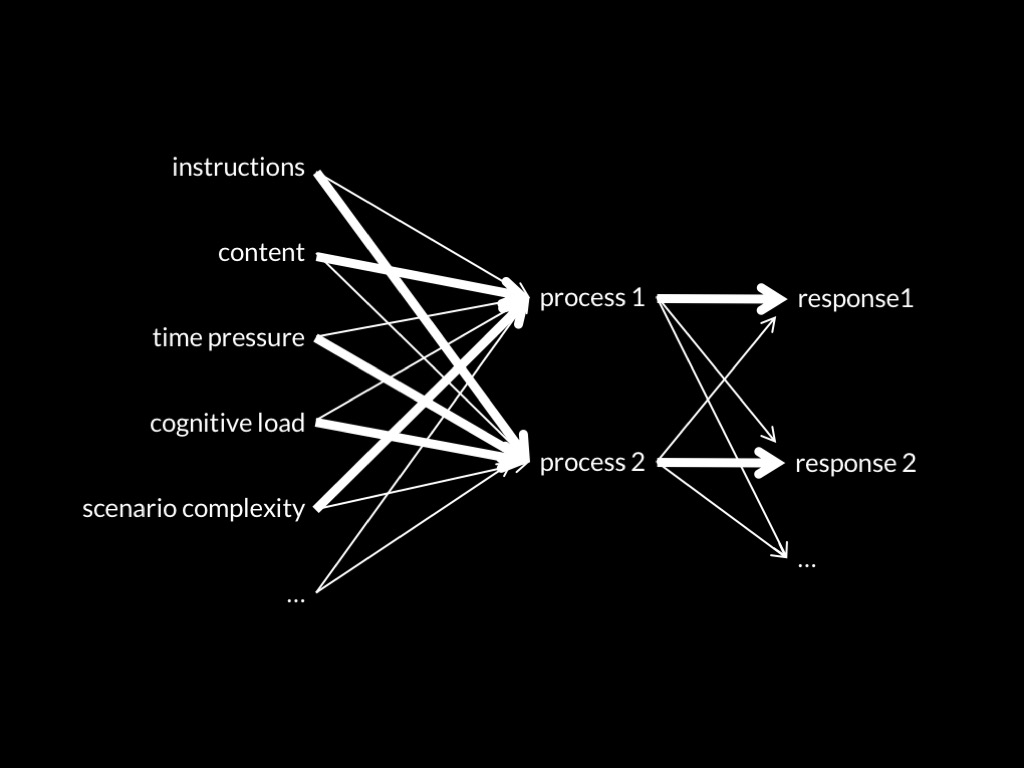

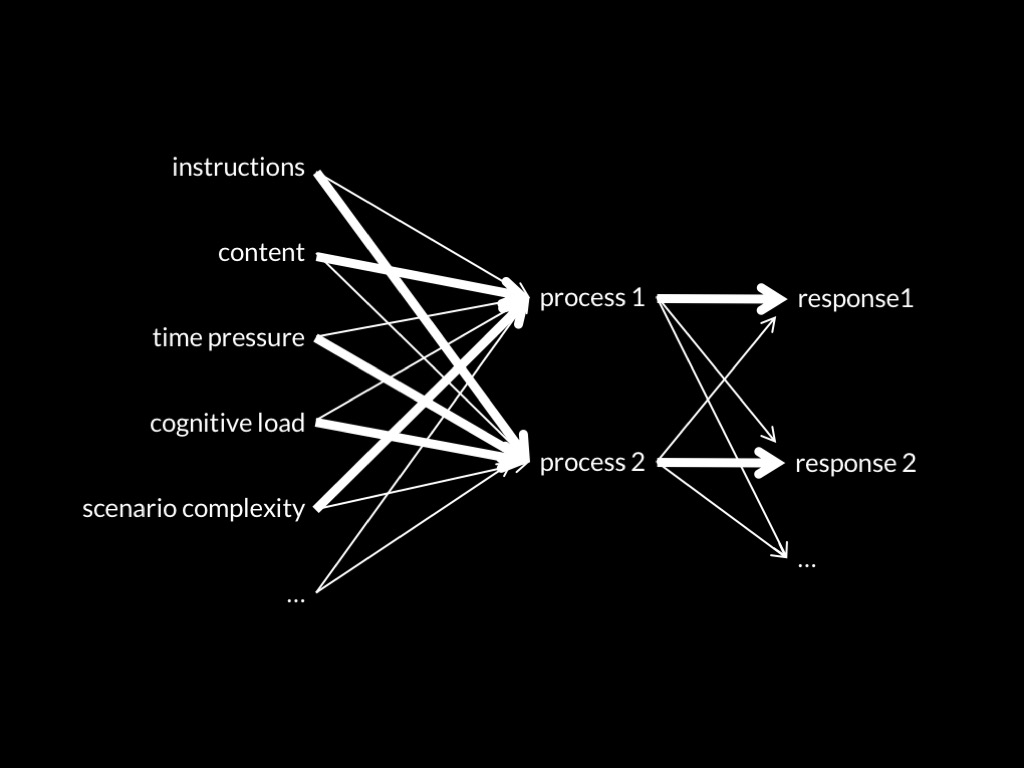

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.

puzzle

[dumbfounding-disengagement] Why are moral judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

1. Ethical judgements are explained by a dual-process theory, which distinguishes faster from slower processes.

2. Faster processes are unreliable in unfamiliar* situations.

3. Therefore, we should not rely on faster process in unfamiliar* situations.

4. When philosophers rely on not-justified-inferentially premises, they are relying on faster processes.

5. We have reason to suspect that the moral scenarios and principles philosophers consider involve unfamiliar* situations.

6. Therefore, not-justified-inferentially premises about particular moral scenarios, and debatable principles, cannot be used in ethical arguments where the aim is knowledge.