Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Conclusion: Yet Another Puzzle

conclusion

How, if at all, does a person’s reasoning influence their moral judgements?

Moral dumbfounding does NOT show that reasoning generally fails to influence moral judgements (contra Prinz, Dwyer and others).

Moral disengagement shows that reasoning plays a substantial (if often tragic) role in people’s moral judgements.

Some, but not all, moral judgements are a consequence of reasoning.

Do emotions influence moral intuitions?

What do humans compute that enables them to track moral attributes?

[emotion] Why do feelings of disgust (and perhaps other emotions) influence moral intuitions? And why do we feel disgust in response to moral transgressions?

[structure] Why do patterns in moral intuitions reflect legal principles humans are typically unaware of?

How, if at all, does a person’s reasoning influence their moral judgements?

[dumbfounding-disengagement] Why are moral judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

one last puzzle

Switch

Vicki [...] notices an empty boxcar rolling out of control. [...] anyone it hits will die. [...] If Vicki does nothing, the boxcar will hit the five people on the main track [...] If Vicki flips a switch next to her, it will divert the boxcar to the side track where it will hit the one person [...]

Flipping the switch is: [extremely morally good:::neither good nor bad:::extremely morally bad]

Drop

Mary [...] notices an empty boxcar rolling out of control. [...] anyone it hits will die. [...] If Mary does nothing, the boxcar will hit the five people on the track. If Mary pulls a lever it will release the bottom of the footbridge and [...] one person will fall onto the track, where the boxcar will hit the one person, slow down because of the one person, and not hit the five people farther down the track.

Pulling the lever is: [extremely morally good:::neither good nor bad:::extremely morally bad]

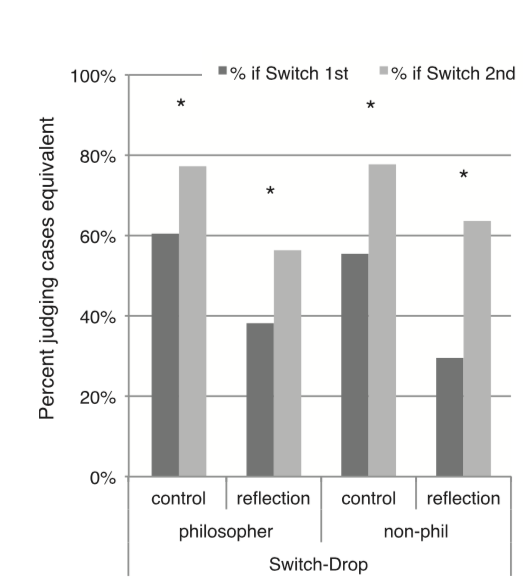

Schwitzgebel & Cushman, 2015 figure 2 (part)

fourth puzzle

[order-effects] Why are people’s moral intuitions about Switch and Drop subject to order-of-presentation effects?

so?

To understand the roles of feeling and reasoning in moral intuitions,

we must identify or create a theory that can solve the puzzles,

is theoretically coherent and empirically motivated,

and generates novel testable predictions.